The snowy albatross (Diomedea exulans) is the largest and most wide-ranging member of the albatross family, Diomedeidae, and one of the most iconic seabirds of the Southern Ocean. Renowned for its immense wingspan and its ability to glide for hours without a single wingbeat, it epitomizes endurance and mastery of wind-driven flight.

This species breeds on remote subantarctic islands such as South Georgia, Crozet, Kerguelen, and the Prince Edward Islands, dispersing across vast circumpolar waters between 30° and 50° south. Long celebrated as the archetypal “wandering” bird, the snowy albatross is a long-lived, slow-breeding species whose survival depends on the stability of marine ecosystems and the preservation of its isolated nesting refuges.

| Common name | Snowy albatross |

| Scientific name | Diomedea exulans |

| Alternative names | Wandering albatross, white-winged albatross, goonie |

| Order | Procellariiformes |

| Family | Diomedeidae |

| Genus | Diomedea |

| Discovery | First described by Linnaeus in 1758; earlier accounts from sailors |

| Identification | Massive seabird with the longest wingspan of any living bird; adults mostly white with black outer wings, pink bill, and pale legs; plumage whitens with age |

| Range | Breeds on subantarctic islands including South Georgia, Crozet, Kerguelen, Prince Edward, Marion, Heard, and Macquarie; ranges widely across the Southern Ocean between roughly 30° S and 50° S |

| Migration | Highly pelagic; disperses widely after breeding, often circumpolar; adults and juveniles may travel hundreds of thousands of kilometers between breeding seasons |

| Habitat | Open ocean and subantarctic waters; nests on remote grassy slopes and coastal plateaus with sparse vegetation and exposure to strong winds |

| Behavior | Masters of dynamic soaring flight; travels vast distances with minimal effort; mostly solitary at sea; pairs monogamous and long-term; interacts with other seabirds and often follows ships for food |

| Lifespan | Average 30-40 years; some individuals exceed 50 years, and theoretical maximum may approach 80 years |

| Diet | Primarily cephalopods, along with fish and occasional crustaceans or carrion; forages mainly by surface-seizing and scavenging |

| Conservation | Vulnerable (IUCN); global population around 20,000 mature individuals, including 6,000 breeding pairs; declining due to longline bycatch, invasive predators, and habitat degradation |

Discovery

The snowy albatross was known to early explorers and sailors long before it received its scientific name. During the 16th and 17th centuries, mariners traversing the Southern Ocean frequently reported encounters with enormous white-winged seabirds. These unclassified “great albatrosses” appeared in ship logs and journals, including those of English navigator William Dampier, who described their immense wingspans and effortless flight.

The species was first formally described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus, who assigned it the scientific name Diomedea exulans. His description was based on a specimen from the Cape of Good Hope, later restricted as the type locality to South Georgia. The genus name Diomedea derives from Diomedes of Greek mythology, whose companions were transformed into birds, while exulans – from Latin exsul, meaning “exile” or “wanderer” – reflects the bird’s extraordinary long-distance movements across the oceans.

Taxonomically, Diomedea exulans represents one of the most complex cases among seabirds. For much of its history, it was treated as a single, wide-ranging species encompassing several populations now recognized as distinct. Until the late 20th century, all large white albatrosses of the Southern Ocean were grouped under D. exulans. In 1983, J.-P. Roux and colleagues proposed that the Amsterdam Island population represented a distinct species, Diomedea amsterdamensis.

Subsequent revisions by J. Warham and D. G. Medway further subdivided the so-called wandering albatross into several regional forms: D. e. exulans, D. e. chionoptera, D. e. antipodensis, D. e. gibsoni, and D. e. dabbenena. Applying taxonomic precedence, D. G. Medway argued that the high-latitude bird of South Georgia and the subantarctic islands should retain the name exulans, while the smaller Tristan-Gough form should become dabbenena.

A major reassessment came with the work of C. J. R. Robertson and G. B. Nunn in 1998, who elevated the former subspecies within the wandering albatross complex to full species based on morphological and distributional evidence. This treatment was subsequently adopted by R. Gales and J. P. Croxall in 1998, and later supported by molecular data.

T. M. Burg and J. P. Croxall in 2004 examined mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite variation, identifying three principal genetic lineages within the complex – Diomedea exulans, D. dabbenena, and D. antipodensis (including gibsoni). Their study revealed virtually no genetic structuring among D. exulans populations across its extensive subantarctic range, but demonstrated clear genetic separation from the Tristan and Antipodean forms.

As a result, current taxonomy recognizes three primary species within the former wandering albatross complex:

- Diomedea exulans (snowy or wandering albatross sensu stricto)

- D. dabbenena (Tristan albatross)

- D. antipodensis (Antipodean albatross, encompassing gibsoni)

The snowy albatross is thus retained as a monotypic species, representing the largest and most wide-ranging of the great albatrosses. Its taxonomic stability today rests on extensive morphological, behavioral, and genetic evidence accumulated over more than two centuries of ornithological study.

Identification

The snowy albatross is among the largest flying birds in the world and the most massive member of the albatross family Diomedeidae. Its body length ranges from 107 to 135 centimeters (42.1-53.1 inches), and its weight varies between 5.9 and 12.7 kilograms (13-28 pounds), depending on sex and breeding condition. The species possesses the widest wingspan of any living bird, averaging about 3.0 meters (9.8 feet) and reaching 3.7 meters (12.1 feet) in some individuals. Unverified historical reports mention exceptional spans up to 4.2 meters (13.8 feet) or even 5.3 meters (17.4 feet), though these remain unconfirmed.

Adult snowy albatrosses exhibit predominantly white plumage that lightens progressively with age. Mature individuals in the so-called “snowy stage” are almost entirely white, with faint gray vermiculations on the upperparts and traces of black only on the distal wing feathers and wingtips. The head and body are pure white, sometimes showing a subtle apricot, pinkish, or yellowish wash on the neck during the breeding season. The underwing is mostly white with a narrow dark trailing edge, while the tail becomes whiter with age. The bill is large and pale pink with a yellowish-horn tip, the iris is dark brown, and the legs and feet are light pink to bluish.

Sexual dimorphism is modest but consistent: males are on average about 4% larger in wing length and up to 20% heavier than females. Adult males typically weigh around 9-11 kilograms (19.8-24.3 pounds), while females average 7-9 kilograms (15.4-19.8 pounds). Males more often attain the fully snowy adult stage, whereas females generally retain small areas of darker plumage on the wings or tail.

Chicks hatch covered in white to pale gray down, with the head and neck typically appearing whitest. As they fledge, they acquire a uniform dark brown juvenile plumage with a contrasting white face, closely resembling the darker members of the wandering albatross complex. Through successive molts, the plumage gradually whitens – first on the underparts and head, then across the wings and back. This transformation is extremely slow, taking more than a decade before males, and occasionally females, reach the fully snowy adult stage. Complete whitening of plumage is typically achieved only by the oldest males.

Vocalization

The snowy albatross possesses a rich and varied vocal repertoire closely tied to its social and courtship behavior. Most vocal activity occurs during elaborate pairing displays, in which sound and movement form a coordinated sequence essential for bond formation and maintenance. Vocalizations are produced by both sexes and include a range of calls, croaks, and mechanical bill sounds.

Typical calls include a powerful expiratory whine, often preceded by a deep inhalation, and a series of croaks, claps, snaps, rattles, and clicks generated by rapid bill movements. These sounds serve multiple functions, from courtship signaling to food-related disputes at sea.

During courtship, individuals perform a stereotyped “dance” composed of distinct vocal and visual elements. The rattle, a rapid volley of pulsed, rubbery clicks made by vibrating the mandibles, expresses excitement or willingness to interact. The snap, a sharp wooden clack, often follows beak-touching gestures and may carry a mild aggressive tone. The sky call, one of the most striking displays, begins with a deep inhalation followed by a loud, drawn-out whine or scream, frequently repeated in succession with raised head and partially extended wings. This call amplifies the bird’s apparent size and is believed to advertise vigor and pair-bond intent. The yammering sequence – fast, aggressive bill-clapping, appears in both territorial and courtship contexts, while yapping, a rhythmic “waa-waa-waa” duet, reinforces established pair bonds.

Together, these vocal and mechanical sounds form a complex acoustic dialogue that underpins the snowy albatross’s highly ritualized social life. Courtship displays combining sky calls, rattles, and yapping duets not only facilitate pair formation but also sustain the lifelong monogamous relationships characteristic of the species.

Range

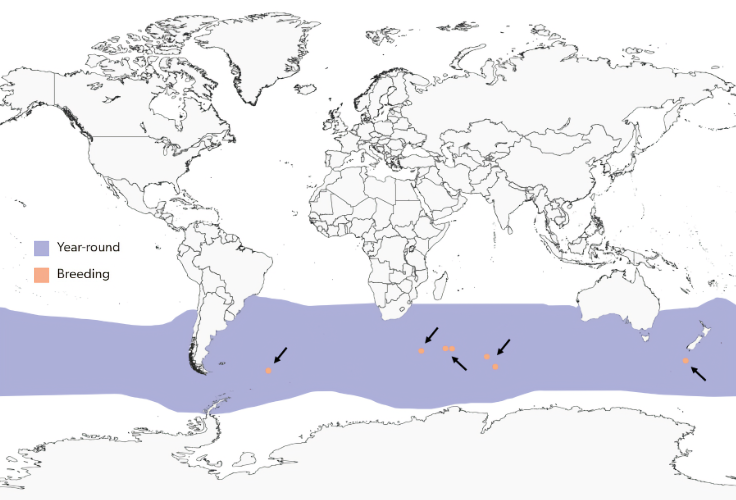

The snowy albatross breeds on a limited number of remote subantarctic islands scattered across the Southern Ocean. Major breeding colonies occur on South Georgia, the Crozet, Kerguelen, Marion, Prince Edward, Heard, and Macquarie Islands. These sites lie primarily between 46° and 55° S, where strong westerly winds and cold, nutrient-rich waters support abundant marine prey.

At sea, the species ranges widely between 30° S and 50° S, though individuals may approach the limits of the Antarctic pack ice or move far north toward subtropical waters. Vagrant birds have been recorded as far north as southern Brazil and even St. Helena (15° S), with exceptional extralimital records from Japan and historical or archaeological finds in Europe. Most northern records involve individuals originating from the South Georgia population, demonstrating the species’ exceptional dispersal capacity.

Migration

After breeding, adult snowy albatrosses disperse widely across the Southern Ocean, often following eastward, wind-assisted circumpolar routes. Many birds appear to perform near-complete circumnavigations of Antarctica, traveling predominantly between 30° S and 50° S. Satellite tracking shows that adults from South Georgia and the Indian Ocean islands frequently revisit specific oceanic sectors between breeding attempts, indicating site fidelity to non-breeding foraging zones.

Migration strategies vary considerably between populations. Birds from the Kerguelen Islands undertake long-distance migrations into the Pacific Ocean, often circling Antarctica two to three times and covering over 120,000 kilometers (75,000 miles) during their non-breeding (“sabbatical”) year. In contrast, many individuals from the Crozet Islands remain largely sedentary, foraging locally within the Indian Ocean. This difference in migratory strategy has reproductive implications: sedentary Crozet birds, particularly females, may breed annually, whereas Kerguelen migrants typically breed biennially.

Young birds are even more wide-ranging. Juveniles leaving the colony embark on extensive dispersal flights, often performing several global circumnavigations before their first return to the natal island. A satellite-tracking study of fledglings from the Crozet Islands showed that juveniles traveled an average of 184,000 kilometers (114,000 miles) in their first year. They tend to occupy lower latitudes than adults, frequently north of 40° S, and exhibit sex-related spatial segregation early in life – young males and females selecting distinct oceanic foraging zones.

Among adults, subtle sex and age differences in distribution persist. Breeding females generally forage farther north than males, while old males are more likely to feed in high-latitude Antarctic waters south of the Polar Front. Despite these variations, all populations demonstrate an extraordinary capacity for sustained long-distance travel, with some individuals completing a full circumnavigation of the globe in less than two months.

Habitat

The snowy albatross is an almost entirely pelagic species, spending most of its life over open ocean far from land. It favors the windy, temperate, and subantarctic waters of the Southern Ocean, where strong westerlies and dynamic air currents allow efficient soaring flight. Individuals occasionally occur closer to shore in parts of the Australasian region, particularly in the Tasman Sea.

During the breeding season, birds return to a small number of remote, low-lying subantarctic islands. They nest on open, gently sloping coastal terrain with sparse tussock or herb cover, often in exposed, wind-swept sites that facilitate takeoff and landing. Studies from Marion Island indicate that elevation, terrain smoothness, vegetation type, and moderate wind strength are key factors in nest-site selection. Nests occur mainly near the coast and are absent from higher, barren interiors above roughly 500 meters (1,650 feet).

Although breeding habitat is limited to such coastal grasslands, the species’ oceanic range spans a vast expanse of water masses, from subpolar to temperate zones, reflecting its adaptation to some of the most dynamic environments on the planet.

Behavior

Outside the breeding season, the snowy albatross is largely solitary, except when aggregating around productive feeding grounds or following vessels. Birds spend over 95% of their lives at sea, with long intervals between colony visits. At breeding sites, they show high site fidelity, returning to the same slope or plateau each cycle, though individuals interact loosely outside courtship contexts.

Albatrosses communicate through body posture and bill movements, which serve to maintain spacing and prevent conflicts. Displays such as head nodding, bill clapping, and wing stretching are common during encounters, both at colonies and at sea. When feeding, individuals are assertive but rarely engage in extended aggression, typically relying on dominance through sheer size.

Locomotion and Flight

The snowy albatross is a master of dynamic soaring, a flight technique that allows it to extract energy from wind gradients above the ocean surface. Using its immense wings, the bird glides for hours without flapping, adjusting its trajectory to maintain lift as it crosses alternating layers of fast and slow-moving air.

GPS tracking studies show that flight performance depends strongly on wind direction and strength. When flying across or slightly into the wind, albatrosses increase airspeed proportionally to wind velocity, but rarely exceed 72 km/h (45 mph), maintaining wing loads within safe limits. They achieve the most efficient travel in moderate to strong westerlies, often tacking into the wind in wide arcs similar to a sailboat. In calm conditions, flight becomes energetically costly, and birds may rest on the sea surface until winds strengthen.

During long foraging or dispersal flights, snowy albatrosses can circumnavigate the globe in under two months, maintaining continuous motion for days at a time. Their remarkable efficiency allows them to sustain ground speeds approaching 130 km/h (81 mph) for extended periods, aided by favorable winds and minimal wing flapping. The species’ flight mechanics – low wing loading, high aspect ratio, and excellent control of pitch and roll – enable near-effortless travel over thousands of kilometers. When on the water, they swim low, using slow paddling movements, and rely on headwinds and slopes for takeoff.

Interspecific Interactions

At sea, snowy albatrosses often feed in loose association with other Procellariiformes, including petrels and smaller albatross species, which they generally dominate. They occasionally follow cetaceans such as orcas and sperm whales, taking scraps from the surface, and frequently trail fishing vessels, attracted by offal and discarded bycatch. Flocks of up to several hundred individuals have been observed near longline operations around the Prince Edward Islands. Despite their size, they may be subject to kleptoparasitism by large skuas, which harass them to steal food.

Predation and Human Relationships

Adult snowy albatrosses face few natural predators, but eggs and chicks are vulnerable to brown skuas, feral cats, and introduced pigs on some islands. Human disturbance and habitat alteration can also lead to nest loss or reduced breeding success.

At sea, the snowy albatross frequently interacts with human activity, particularly around fishing vessels, which it follows in search of discarded fish and offal. These birds often gather behind trawlers and longliners, gliding effortlessly above the wake and seizing floating scraps. Such behavior illustrates their adaptability and opportunistic foraging habits in an environment increasingly shaped by human presence. Occasional close encounters have made the species a familiar, if rare, sight to sailors traversing the Southern Ocean.

Breeding

The snowy albatross is a monogamous species that typically breeds biennially. Pairs usually remain bonded for life, though occasional divorce and extra-pair copulations (up to 11% in some colonies) have been documented. Following the loss of a partner, birds may delay re-pairing for up to three years.

Sexual maturity is reached at 9-11 years, with males maturing slightly later than females. Young birds begin returning to their natal islands at 5-7 years of age but may spend several non-breeding seasons courting before their first successful reproduction. Breeding success and frequency vary among individuals: some birds adhere to a strict biennial rhythm, while others attempt quasi-annual breeding, especially after failed nesting attempts.

Courtship

Courtship in the snowy albatross is an elaborate and highly ritualized process, serving both partner selection and long-term bond reinforcement. Unpaired birds gather at traditional display sites on breeding slopes, where females initiate most interactions by approaching males and performing a sequence of greeting gestures. These “dances” consist of 22 distinct movements and vocalizations, including head forward postures, touch beak, rattle, snap, sky call, and yapping. The displays combine visual posturing – arched necks, wing extensions, synchronized preening, with vocal signals, such as rattling mandibles or resonant calls delivered with upturned bills.

Display bouts last from a few seconds to about 15 minutes, with those including sky calls lasting longer. Males and females often mirror each other’s movements, and many sequences end peacefully with the pair sitting together and duetting. Over time, display frequency declines as bonds strengthen, replaced by yapping duets and allopreening, which serve as mechanisms for pair recognition and maintenance.

Personality differences also play a role in long-term pairing: studies indicate that shyer males are more likely to experience divorce than bolder individuals, suggesting behavioral traits influence mate retention and competition within colonies.

Nesting

Breeding colonies are loosely structured, with nests spaced tens of meters apart, usually forming small clusters of up to 30 nests per hectare. Birds nest on open, gently sloping terrain with sparse tussock vegetation, often near the coast or on low plateaus where strong winds facilitate takeoff. Nests are ground-built truncated cones made of mud, grass, and plant material, measuring roughly 100 centimeters (39 inches) in diameter at the base and 50 centimeters (20 inches) at the top.

Pairs show high site fidelity, often reusing or rebuilding the same nest in subsequent seasons. The breeding season begins in November, when males return to the colony about a month before females. After a brief pre-laying exodus lasting 5-18 days, egg laying occurs mainly between mid-December and mid-January across most colonies.

Egg Laying and Incubation

Each pair lays a single egg per season, averaging 490 grams (1.1 pounds) and measuring about 12 centimeters (4.7 inches) in length and 8 centimeters (3.1 inches) in width. The egg is whitish with faint reddish spotting near the broader end. Both sexes share incubation duties for about 78-80 days, alternating stints of 2-3 weeks each, with males contributing just over half of the total time.

Hatching and Parental Care

Chicks hatch from March onward, covered in white to pale gray down with a whiter head and neck. They are brooded for 4-5 weeks, during which time one adult remains at the nest while the other forages and provides food. Feeding frequency varies by site – on average every three days at South Georgia and every two days at the Crozet Islands. Each chick receives a total of 60-65 kilograms (132-143 pounds) of food over the rearing period, slightly more than half of it provided by males.

Fledging occurs after approximately 270-280 days, typically in December, when the chick reaches a weight of about 8.9 kilograms (19.6 pounds) occasionally exceeding 11 kilograms (24.3 pounds) at peak mass before losing fat reserves prior to departure. Heavier chicks usually fledge earlier. Experienced parents brood longer and provision more effectively, increasing chick survival. Once fledged, young birds begin a prolonged oceanic phase lasting several years before returning to the colony to begin their own courtship cycles.

Lifespan

The snowy albatross is one of the longest-lived birds in the world. Average lifespan is estimated at 30-40 years, though many individuals exceed this, and one bird breeding on Prince Edward Island was known to be at least 50 years old. Given low annual adult mortality of only 3-7%, theoretical models suggest that some individuals could live up to 80 years under favorable conditions. Such exceptional longevity is typical of large, slow-breeding seabirds, whose survival depends on sustained adult lifespan rather than frequent reproduction.

Mortality is highest during the early years of life. Survival to fledging at South Georgia has declined from about 36% in the late 1950s to 27% in the 1980s, reflecting environmental changes and the ongoing influence of fisheries. Adult mortality, while naturally low, varies with sex, breeding status, and exposure to anthropogenic pressures.

Studies indicate that female albatrosses experience higher mortality in some populations, largely due to greater overlap with fishing areas, resulting in a male-skewed adult population. This imbalance contributes to higher widowhood rates among males and more frequent divorce events among females, both of which can reduce lifetime reproductive success.

In natural settings, predation on adults is rare, but eggs and chicks are vulnerable to brown skuas, feral cats, and pigs on some islands. Historically, a small number of adults were taken for bait or food, but direct persecution is now uncommon. The greatest external influence on mortality remains incidental capture in longline fisheries. Despite these pressures, the snowy albatross continues to exemplify longevity and resilience, its lifespan reflecting an evolutionary balance between extreme endurance, low fecundity, and long-term pair fidelity.

Diet

The snowy albatross feeds mainly on cephalopods and fish, occasionally supplementing its diet with crustaceans, carrion, and offal. Squid dominate across most colonies, forming 32-77% of the diet by mass, with fish contributing 15-46% and crustaceans less than 1%. The diet is dominated by large deep-water squids, particularly Moroteuthopsis longimana (previously Kondakovia longimana), as well as glass squids (Taonius), cock-eyed squids (Histioteuthis), and the Argentine shortfin squid (Illex argentinus).

The species’ diet is broadly consistent across its range, from South Georgia and the Crozet Islands to Marion and Macquarie, but regional variation occurs in cephalopod composition; for example, birds at Macquarie Island consume at least 18 species of squid, four of which are not recorded elsewhere.

Feeding and Foraging Tactics

The snowy albatross forages by surface-seizing prey and occasionally makes shallow plunges to about 1 meter (3.3 feet) below the surface, sometimes pursuing items briefly underwater. Olfactory cues play an important role in prey detection, triggering nearly half of all capture attempts. Individuals forage both day and night, but feeding activity often peaks after dusk, when smaller, bioluminescent squid migrate upward in the water column. Larger, non-bioluminescent squid are usually captured during daylight.

The species travels enormous distances between feeding events – on average 64 kilometers (40 miles) apart, and only a small portion (about 27%) of prey are taken in localized feeding patches.

Scavenging is an important component of its foraging strategy. Many cephalopods eaten are species that float after death, indicating that carrion and fishery discards represent a substantial proportion of total prey mass. Birds frequently feed near fishing vessels, alongside other seabirds and cetaceans, exploiting offal and bycatch. Compared to smaller albatrosses, the snowy albatross scavenges more often, likely due to its larger size and dominance at mixed-species feeding aggregations.

Variation and Dietary Shifts

Despite interannual fluctuations in prey availability, long-term studies at South Georgia show a remarkably stable cephalopod assemblage in the albatross’s diet over more than a decade. Kondakovia longimana consistently dominates by mass (60-89%), suggesting that the species is well buffered against short-term changes in prey abundance. However, subtle spatial differences exist: individuals foraging in Antarctic waters take primarily “Antarctic” squid species, whereas those near subantarctic islands incorporate more temperate taxa and fish. These shifts reflect foraging latitude and oceanic productivity rather than true dietary specialization.

When rearing chicks, adults adjust their foraging patterns, mixing short (around 5 days) and long (over 6 days) trips to balance provisioning and self-maintenance. While brooding, most feeding occurs within 300 kilometers (190 miles) of the breeding islands, but during incubation, foraging trips may exceed 15,000 kilometers (9,300 miles). Males deliver slightly more food overall, whereas females tend to travel farther between feeding events.

Culture

The snowy albatross has long held a special place in maritime tradition and human imagination. Its immense wingspan and habit of following ships across vast distances made it a familiar companion to generations of sailors, who viewed it as a symbol of luck and guidance. Many believed albatrosses carried the souls of lost seafarers, and harming one was thought to bring storms and misfortune.

The species entered literary history through Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), where the killing of an albatross brings a supernatural curse upon a ship and its crew. Though the poem does not specify a species, its description of a large, white-plumaged, far-ranging seabird strongly evokes D. exulans. From this tale arose the enduring metaphor of “an albatross around one’s neck,” symbolizing guilt or burden.

Among Maori communities of New Zealand, albatrosses held cultural and practical importance – their bones fashioned into tools and ornaments, and their feathers used in ceremonial garments. While the snowy albatross itself breeds farther south, its occasional presence in subantarctic waters contributed to its symbolic value in seafaring cultures.

Today, the snowy albatross stands as a flagship species for global seabird conservation, representing the challenges of longline bycatch, habitat change, and oceanic pollution. It endures in both science and symbolism as an emblem of freedom, endurance, and the wild power of the Southern Ocean.

Threats and Conservation

The snowy albatross is currently classified as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, reflecting a rapid population decline over the past three generations (roughly 70 years). The global breeding population is estimated at around 6,000 breeding pairs, equating to roughly 20,000 mature individuals. This represents a marked reduction from the late 1990s estimate of approximately 8,500 pairs.

Populations at South Georgia have declined most steeply – by about 30% between 1984 and 2004 and a further 18% by 2015, while colonies at the Crozet and Kerguelen Islands stabilized briefly in the 1990s before resuming a downward trend. Populations at the Prince Edward Islands are currently stable, and only a few pairs now breed on Macquarie Island.

Main Threats

The principal threat to the snowy albatross is incidental capture (“bycatch”) in longline and trawl fisheries, which reduces both adult survival and juvenile recruitment. Longline hooks attract birds as they seize bait from the surface, often leading to drowning. This single factor has driven population crashes in several regions – such as a 54% decline on the Crozet Islands between 1970 and 1986, and continues to cause heavy losses, especially for birds dispersing from South Georgia into the southwest Atlantic.

Populations breeding at the Crozet, Kerguelen, and Prince Edward Islands are also at risk from pelagic fisheries in the Indian Ocean and Tasman Sea. Even minimal bycatch rates can have long-term impacts due to the species’ slow reproduction and small global population.

Additional pressures include introduced predators at nesting sites. On Kerguelen, feral cats occasionally cause complete breeding failure in affected colonies, while house mice attack chicks on Marion Island, affecting about 1% of the population annually. Habitat degradation from trampling by fur seals has altered nesting areas at South Georgia, and marine pollution poses emerging risks as chicks sometimes ingest plastic debris or discarded hooks. Historical harvesting by sealers and bait collectors further reduced some island populations, though such exploitation has largely ceased.

Climate variability and shifting oceanographic conditions add further stress, influencing prey availability and adult survival. Rising sea-surface temperatures and changes in wind patterns are projected to alter key foraging zones, potentially compounding declines over coming decades.

Conservation Efforts

The snowy albatross benefits from substantial international protection. It is listed under Appendix II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and Annex 1 of the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP). Long-term population monitoring and satellite-tracking programs operate across major breeding sites, including South Georgia, Crozet, Kerguelen, the Prince Edward Islands, and Macquarie Island. Within these regions, several management actions have achieved measurable success:

- The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) implemented mitigation measures (e.g., weighted lines, night setting, bird-scaring lines), reducing albatross bycatch around South Georgia by over 99%.

- The Prince Edward Islands are protected as a Special Nature Reserve, and Macquarie Island is a World Heritage Site where cats, rabbits, rats, and mice have been successfully eradicated.

- Large parts of the Crozet and Kerguelen Islands now fall within a designated nature reserve, restricting access and disturbance.

Future Outlook

Although conservation measures have reduced some immediate threats, the snowy albatross remains in decline across much of its range. Its recovery depends on maintaining strict fishery mitigation practices across all ocean basins, continued eradication of invasive species on breeding islands, and expanded tracking and demographic studies to identify vulnerable foraging areas. With its slow life history and small population, any increase in adult mortality can quickly offset gains from local protection. Sustained international cooperation remains essential to ensure that this emblematic species of the Southern Ocean continues to soar over the world’s most remote waters for generations to come.